Visiting the Yucatan, Homeland of the Northern Lowland Maya

Cancun is one of the busiest tourist destinations in the world. People come for the beaches and sun. The Yucatan Peninsula also has incredible archeology.

The Deep Past.

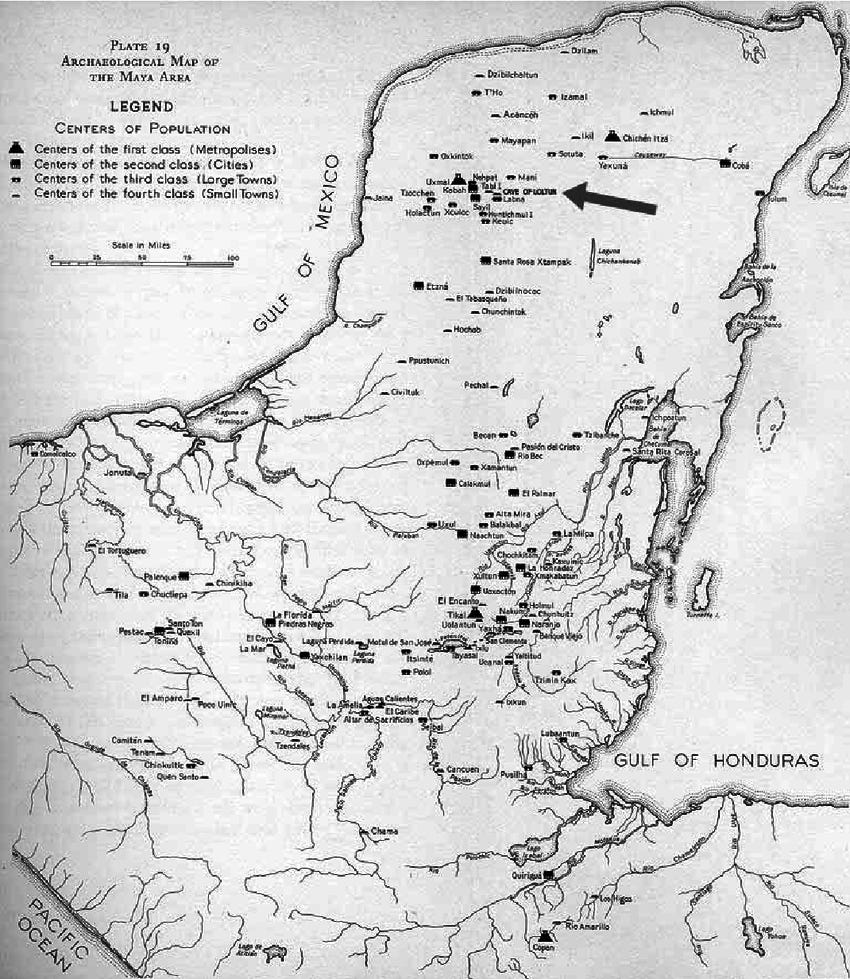

The Yucatan Peninsula, shown here, is the easternmost part of Mexico. It is bordered on the east by the Caribbean Sea. On the west and north by the Gulf of Mexico. And on the south by the mountainous spine of Central America.

Situated in the tropics it has two seasons. A cool dry season from December to May, when there is no rainfall. And a hot wet season from June to November of daily rainfall.

Geologically the peninsula is basically a giant slab of limestone.

It is the remains of a series of gigantic reef systems that have formed and reformed here as ocean levels have risen and fallen over the millennia. Understanding this geology is necessary for understanding everything about life in this place since humans first started living here sometime in the last 20,000 years.

Karstic (limestone) geologies have some distinctive characteristics. Firstly, they are porous.

Rainwater falling on them sinks into the ground rapidly, like water being poured on a sponge.

Secondly, they are soft and dissolve easily in weakly acidic solutions.

Rainwater, reacting with CO2 in the air and the calcium in the limestone, forms a weak solution of carbonic acid as it drains through the limestone bedrock. So, as it drains, it dissolves the rock and creates vast underground cave systems in the limestone.

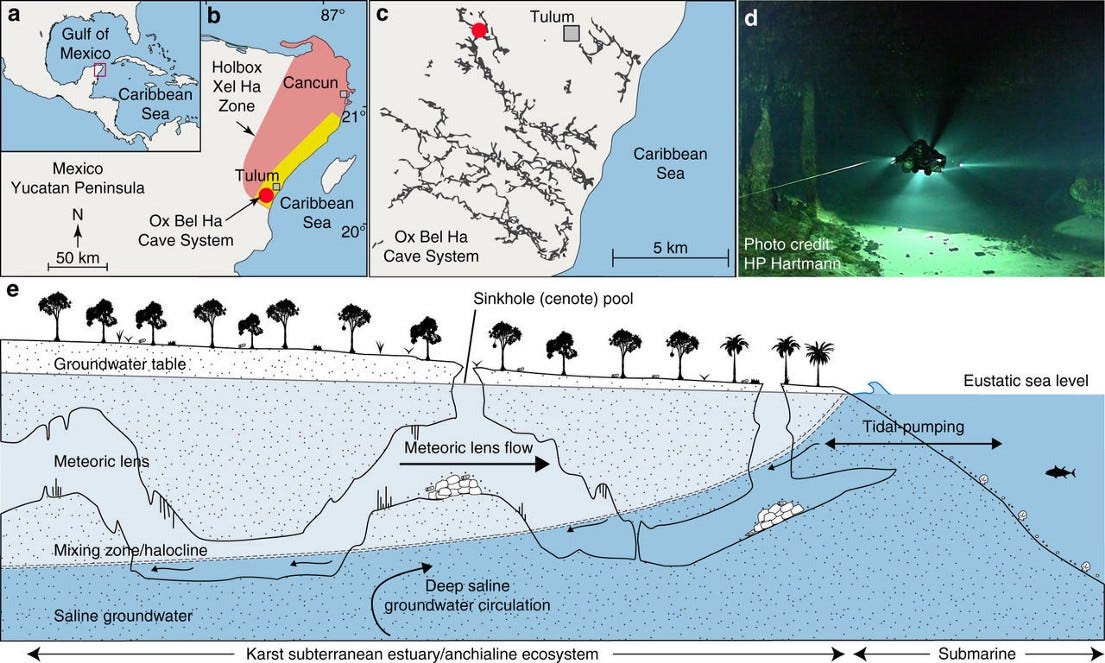

Shown here is a map of some of these huge cave systems that form a vast underground river and lake network beneath the surface of the peninsula.

On the surface during the rainy season, the countryside is covered in lush green jungle. Which makes it is easy to imagine an idyllic life as a hunter gatherer here. However, this lush countryside is a deceptive deathtrap.

Because of the geology, rainfall sinks into the ground almost immediately. There are no rivers, no streams, and no lakes. The only surface water is found in occasional shallow ponds (called bajo’s) that form in low spots where clay soils have built up and prevent the water from draining away. That brown spot in the middle of the photo is a bajo.

During the rainy season, when it rains almost daily, this is a manageable issue. During the dry season, when there is no rain for six months and the bajo’s dry out, this lack of water becomes a matter of life or death.

So how do animals and people survive here during the dry season? How do they access the water that has gone underground?

The answer is the cenote.

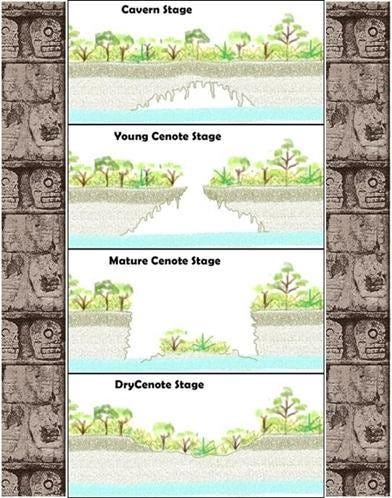

A cenote, or sinkhole, forms when the rock below the surface erodes away and forms a cavern. When the roof collapses, you have a big hole in the ground which is called a cenote.

Cenotes are everywhere in the Yucatan but many do not have water in them, or the water is inaccessible from the surface. Finding a cenote with accessible water is crucial to surviving the long dry months.

The cenote shown here is the main cenote at Chichen Itza, a large Maya city. As you can see, it is large (about 100’ across), the sides are very sheer, and it is about fifty feet down to the water.

The Maya built\carved stairs down to the water. But keep in mind, that in a society without pumps, every gallon of water taken out of that cenote had to be hand carried back up those steps.

Getting water during the dry season was a labor-intensive process, and this is an easy cenote to access. It can be much, much more difficult to get water from a cenote.

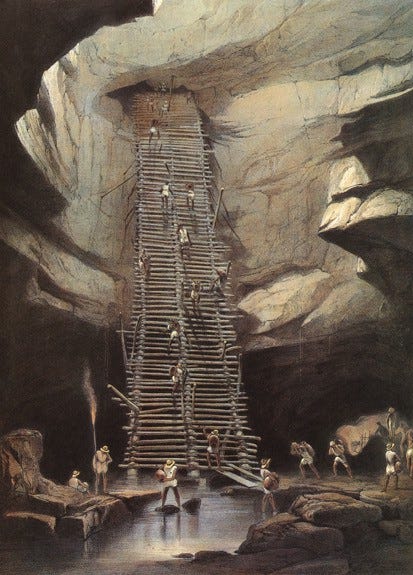

This painting by Frederick Catherwood was done in 1844 as an illustration for the book “Incidents of Travel in Yucatan Vols. 1 and 2” by John Lloyd Stephens. Stephens and Catherwood went to the cenote at Bolonchen (Village of Nine Wells) to observe how water was obtained during the dry season.

The arduousness of going into the caves through narrow, dark, humid, hot passages with an 80’ descent on a wooden ladder at the end of the trek is described in their book but this illustration is worth a thousand words. They marveled that the men of the village would do this almost daily, but it was the only source of water for miles around.

Descents like this, into the underworld to bring back water, were an inescapable feature of life in the Yucatan in the premodern world.

BTW: If you are interested in the archeology and history of the Yucatan, Stephen’s book is a great read and still relevant, even today. I highly recommend it.

The last important piece of the geology to understand is how sea level affects the water level in the cenote cave systems. The Wikipedia entry on the geology of the Yucatan explains it as follows:

“The Yucatán Peninsula contains a vast coastal aquifer system, which is typically density-stratified. The infiltrating meteoric water (i.e., rainwater) floats on top of higher-density saline water intruding from the coastal margins. The whole aquifer is therefore an anchialine system (one that is land-locked but connected to an ocean). Where a cenote, or the flooded cave to which it is an opening, provides deep enough access into the aquifer, the interface between the fresh and saline water may be reached. The density interface between the fresh and saline waters is a halocline, which means a sharp change in salt concentration over a small change in depth.

The depth of the halocline is a function of several factors: climate and specifically how much meteoric water recharges the aquifer, hydraulic conductivity of the host rock, distribution and connectivity of existing cave systems and how effective these are at draining water to the coast, and the distance from the coast. In general, the halocline is deeper further from the coast, and in the Yucatán Peninsula this depth is 10 to 20 m (33 to 66 ft) below the water table at the coast, and 50 to 100 m (160 to 330 ft) below the water table in the middle of the peninsula, with saline water underlying the whole of the peninsula.”

In simpler terms, this means that there is a layer of fresh water (light blue in diagram above) that in essence “floats” on top of a layer of salt water (dark blue). When sea level goes down, the fresh water floating on top of it also goes down, and water drains out of the underground cave systems. When the sea level goes up, the salt water “lifts” or “pushes” the fresh water higher, and the cave systems flood.

This vast watery underworld is a unique ecosystem found nowhere else in the world. Exploring and mapping it has been a decades long project of dedicated amateur cave divers\explorers.

This is a very dangerous type of diving with no room for mistakes. If you lose your light, you will probably die. If you get lost, you will probably die. If you knock some rocks loose and they fall on you, you will probably die.

DO NOT TRY THIS ON YOUR OWN, EVER.

Understanding the geology of the Yucatan gives its archeology context.

People have been occupying the Yucatan peninsula for a very long time. Much longer than most people realize. There are two sites on the peninsula that make clear just how long people have been living here. Hoyo Negro near Tulum, and the Loltun Cave near Kabah.

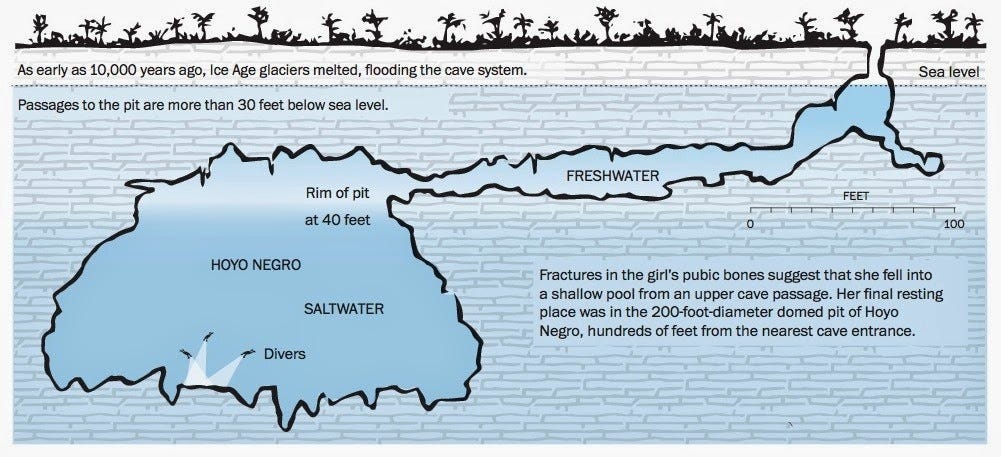

At Hoyo Negro in 2007 cave divers found the oldest human remains in North America. Named Naia, the bones were those of a young girl who had fallen into a natural pit trap and died around 11,000 BCE (13,000 years ago).

Analysis of her bones revealed that she was 15 or 16 at the time of her death. She had given birth about a year before her death and she had suffered from several episodes of malnutrition\starvation as a child. Life at the end of the last ice age was apparently not easy.

At Loltun Caves, in the Puuc region near Kabah, you can take a tour of caves that have evidence of human usage since around 10,000 BCE. Stone tools and the bones of mammoths and bison are the earliest artifacts, but you can also see handprints on the cave walls, that carbon dating places between 7,000 to 8,000 BCE.

People have been occupying the Yucatan since the last ice age came to an end.

The Hoyo Negro turned out to be a treasure trove of ice age animal bones. Like the famous La Brea tar pits of Los Angeles, it was a natural trap.

Animals coming into the cave looking for water would fall off the cliff, down 100 feet, and die. In the anaerobic (oxygen poor) water at the bottom of the pit their bones were perfectly preserved. Shown here are all the animals whose bones were found. A snapshot of the Yucatan ecosystem circa 11,000 BCE.

The divers were understandably thrilled by their discovery but then the unbelievable happened; they saw a human skull on the cavern floor.

What they had discovered was the almost complete skeleton of a young woman from the end of the ice age, 13,000 years ago. They named her Naia and her remains are the oldest human remains ever discovered in the Americas.

People have been occupying the Yucatan for a very long time. Eventually, as the climate changed and the megafauna died off, they abandoned the hunter\gatherer lifeway and took up a more settled agricultural lifeway.

They became part of a broad grouping of people who were related linguistically, culturally, and ethnically. They became the Maya.

-rc 021923

If you want to read more about the Maya, the Yucatan, and Mesoamerican/South American/New World Archeology sign up for emails when I post here. This content will always be free to everyone. Archeology is my passion.