The Roads of the Maya

The Maya built a road network that rivals the Romans. In the Yucatan it's only visible in a few places. It was HUGE.

Sacbe (pronounced sock-bay) is Maya for “white road”.

Sacbeob (pronounced sock-bay-oob), Maya for “white roads”, are found throughout the Maya world. This one is typical of those found in the Puuc hills, several hundred miles to the west of Coba.

This excavated and restored segment of road is at the city of Chichen Itza. The environment is the same as Coba’s and the technique of road construction is the same. Two stone retaining walls holding a causeway style, elevated roadbed, with a stuccoed cap applied as surfacing.

Roads are important markers of societies and civilizations. Roads make it possible to efficiently move people and goods from place to place. They make it possible to move armies rapidly. They make possible the exchange of information and news and they help make societies cosmopolitan and dynamic.

Roads are important but they take a lot of effort to build. They are generational “long term” projects that take sustained funding and a stable labor force to pull off. The roads of the Maya were not hard packed dirt paths through the jungle, or simple graveled trails. They were carefully engineered and constructed. They match the best roads in the world built by anyone in any time frame.

The diagram above shows a cross section of the standard technique the Maya used for road building throughout their cultural sphere of influence. These were well designed, carefully engineered, all weather roads. Meant to stand up to heavy usage and meant to last. Building a road like this was a major undertaking.

The Maya built a lot of them.

The Sacbeob of Coba, a Maya city of the Yucatan

This map shows Coba’s known road network. All the straight lines that you see are sacbe. All of them were built to the same standard and with the same technique described above. They tied the central core of Coba to it’s outlaying agricultural towns and villages. They also linked Coba into the larger Maya world.

In the upper left of the map is sacbe number one, the road to Yaxuna. Sacbe number one, which connected Coba to Yaxuna, was the longest known road in the Maya world for decades after it was discovered.

Called the Yaxuna-Cobá causeway, or Sacbe 1, it is of one the longest known sacbe in the Maya world. It is one hundred kilometers (62 miles) long and connects the Maya centers of Cobá and Yaxuna.

Along Sacbe 1’s east-west course are water holes (dzonot), stele with inscriptions, and several small Maya communities. Its road bed measures approximately 8 meters (26 feet) wide and is typically 50 centimeters (20 inches) high, with various ramps and platforms alongside it.

Recent investigations by Loya Gonzalez and Stanton (2013) suggest that the sacbe’s main purpose was to consolidate Coba’s hold on the large market center of Yaxuna to control trade throughout the peninsula. Completed in the 600’s when Coba was at the height of its power, it established Coba as one of the major powers of the Yucatan peninsula.

Coba has an exceptionally large road network but all major Maya cities have road networks associated with them. These roads had two functions. The shorter ones connected the urban cores of the cities to the satellite towns that provided them with agricultural products. The longer ones plugged cities into the vast trading networks that moved goods throughout Mesoamerica.

How big was the Maya road network?

How large the Maya road network is believed to have been, is suggested by this map of the road and rail network around the city of Merida (which was the Maya city of T’ho when the Spanish arrived) in the state of Yucatan. The authors of a research paper in 2005 argued that most of these roads and railway lines were built over preexisting Maya roads.

The basis of their theory is an earlier study, done in the US, that found about 60% of the roads east of the Mississippi were built over Native American trails\roads. The Maya had built a network of excellent elevated roadbeds that were ready to use. So, they argue that 19th century Mexicans did what societies usually do to the ruins of older civilizations, they recycled them.

Even if you do not accept the idea of a road network as big as the one posited in this theory, there is no doubt that the Maya built a lot of roads. Recent discoveries using LiDAR technology, which allows archeologists to see through vegetation, have revealed massive road networks in Guatemala. Among some of earliest Maya city states.

LiDAR analyses in the contiguous Mirador-Calakmul Karst Basin, Guatemala: an introduction to new perspectives on regional early Maya socioeconomic and political organization Cambridge University Press 120522

Ancient Maya cities, 'super highways' revealed in latest survey Reuters 011623

A new study has revealed nearly 1,000 ancient Maya settlements, including 417 previously unknown cites linked by what may be the world's first highway network and hidden for millennia by the dense jungles of northern Guatemala and southern Mexico.

It is the latest discovery of roughly 3,000-year-old Maya centers and related infrastructure, according to a statement on Monday from a team from Guatemala's FARES anthropological research foundation overseeing the so-called LiDAR studies.

The finds date to the so-called middle to late pre-classic Maya era, from around 1,000-350 BC, with many of the settlements believed to be controlled by the metropolis known today as El Mirador. That was more than five centuries before the civilization's classical peak, when dozens of major urban centers thrived across present-day Mexico and Central America.

This is important at Coba, because Coba has one of the largest number of sacbe ever found in a single Maya city.

Why Roads?

There are a lot of misconceptions about the roads of the Maya. People ask, “If the Maya didn’t have the wheel, what was the purpose of the roads?” There were theories that the roads were just for troop movements or religious processions. Many find the presence of these roads “highly mysterious” and “unexplainable” and suggest “aliens” had the Maya build them so that their vehicles could move from city to city.

The common assumption is that Native American cultures, including the Mesoamerican, didn’t have the technology of the wheel and without wheeled vehicles a road is useless.

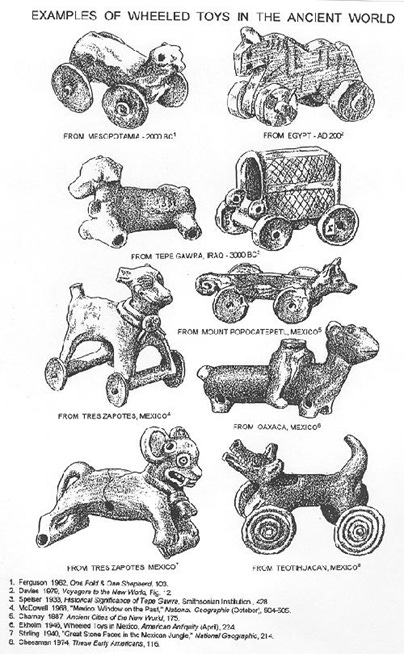

The problem with these assumptions is that they are not true. It is a misconception that the wheel was unknown in Mesoamerican and other Native American cultures.

This small toy on display at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City has, not just wheels, but an axle as well. Mesoamerican cultures clearly knew what a wheel was and how to use it.

Here is another example from Villahermosa in the state of Tabasco.

This one is from the Aztec period (1300–1400 CE) and was found in Central Mexico.

Finally, here is a comparison of small wheeled toys from all over Mexico with examples from Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Iraq.

Clearly these cultures, both Old World and New World, had the wheel. So, if the Mesoamerican cultures knew what a wheel was and how it could be used, why didn’t they use it to make wheeled vehicles? Wouldn’t that have made it easier to transport goods from place to place?

Geography was Destiny

It’s easy to forget, because we live in a world in which the ecologies of the Americas have been massively altered due to the Columbian Exchange of plants and animals. But, prior to the arrival of the Spanish there were no large domesticated animals in the Americas (with the exception of the Llama).

No horses, no cattle, no sheep, no pigs, no goats. None of the barnyard animals that define Eurasian farming and herding cultures existed in the Americas. There were no shepherds tending their flocks, farmers yoking their oxen to plow their fields, pigs in their pens, and most importantly there were no horses to pull a cart.

Instead they moved goods like this;

In place of wheeled carts, goods in Mesoamerica were moved by merchants like this. On foot, with packs on their backs. These packs would have been about 75 to 100 pounds with a tumpline around the forehead to help make the load more manageable.

This may seem inefficient, but remember, at any given moment there would have been hundreds of thousands of these merchants on the roads. On good roads, they would probably been able to do 20–25 miles a day.

Here is a Maya depiction of a “merchant’s pack”;

Shown on the right, we can see that the merchant pack was large and well designed. It has a wooden frame and a clever pop out support to hold it upright. Ropes fasten a variety of items on the sides and there would have been space in the pack to hold bags of other goods.

These traders, in their hundreds of thousands, in conjunction with the shipping trade moved goods throughout Mesoamerica. The great roads of the Maya are a testament to the volume and extent of that trade. A trade network that Coba was an integral part of for hundreds of years.

You can make the argument that no matter how good these traders were at moving goods around with packs, carts would have been better. However, it has not been proven that a cart would be any better than a pack, even on a road. Without any animals to pull a cart, it would have had to have been pulled by the trader and his assistants.

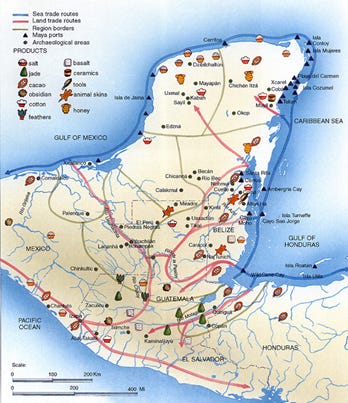

A cart could hold more, perhaps, but pulling a heavily laden cart might be much slower than just walking with a pack on. Also, if you examine the map of Mesoamerican trade patterns you can see that the types of goods being moved around the trade networks are low bulk, high value items.

Things like timber, corn, and building materials are sourced locally by cities. The goods that the traders were carrying were for the most part luxury goods, obsidian, and salt.

These are the types of goods that can be carried on someone’s back that would generate high profits. While trader’s in these goods might have roads to move on some of the time. It seems likely that there would be times that they would have to leave those roads to reach secondary markets in smaller communities.

At that point, a cart would be useless. Keeping everything on his back would give a trader the most flexibility in choosing his path.

What we can say for sure, is that cultures with draft animals go from playing with wheels, to making carts. Cultures without those animals do not.

However, they still make roads.

Which brings us back to the sacbe of Coba.

After this long discussion of sacbe and what an incredible feat of engineering and social organization they represent, the optics of them are somewhat underwhelming.

This trail is Sacbe 9. That’s what the people in this picture are walking on. It was once 20 meters wide and surfaced with an all weather, pebbled, white stucco. It may not look like much after 1,500 years, but the presence of roads like this made Coba a powerhouse city, both economically and politically for hundreds of years.

Roads like that are what tied together Mesoamerica. The total amount of roads built in the Mesoamerican cultural area is staggering. It is on par with the road networks of Ancient Rome and Imperial China.

Which leads one to wonder, what will remain of our roads in 1,500 years?

-rc 021923