Exhibits in an Atrocity Museum.

A place for things that, "should never be forgotten".

So, this is the way my brain works sometimes.

I read an interesting piece by Adebayo Adeniran on Medium.

It made me think of the Biafran War of the 60’s and what an atrocity that was. How it’s almost been forgotten.

How so many other atrocities of the 20th century are being forgotten.

I love graphic novels.

Finder, by Carla Speed McNeil, is in my personal canon of the great works of this artform. It’s brilliant. Right up there with Neil Gaiman’s EPIC story cycle “Sandman”, the anarchist politics of Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta, the furious defense of Liberal Ideals by Warren Ellis in Transmetropolitan, and the immersive world building of Mark Smylie’s Artesia.

The link between these two threads is the Atrocity Museum.

In “Finder” there is an “Atrocity Museum” in the city. It’s not what you imagine. There are no exhibits.

You go into a plain empty room. You stand alone in silence.

You tell your story. Your testimony.

At the end, the room asks for your identity and for details. The whole building is one giant AI. It is designed to collect and store personal memories from people who participated in an atrocity. Victim or perpetrator, it doesn’t care.

If you want, you can hear the testimonies of others. From either side.

The museum is a confessional and a monument. Indestructible, self powered, and sentient it was built to preserve the memories of these events. So that they could never be completely forgotten, so that the testimony would endure.

Which made me think about Cultural Artifacts.

We tend to visualize cultural artifacts as buildings, religious art, sculpture, and paintings. Things you put in a museum or preserve in place. There are other forms of cultural artifacts and I would argue that in the instance of Atrocities, physical museums may not be the most effective way of preserving memory.

Anthony Burgess (A Clockwork Orange) in the 70’s wrote an impassioned essay on the need for an Atrocity Museum. However, he imagined something far more dire and far more physical for museum visitors than the Atrocity museum of Ms. McNeil.

I have always wondered if this essay inspired Alan Moore when writing “V for Vendetta”. After all, what is Evey’s transformation at V’s hands, if not a stay in an Atrocity Museum as imagined by Burgess?

Nick Bantock in his work “The Museum at Purgatory” (1999) also played with this concept. As have others, both artistic and scholarly.

It is revealing that we now have a corpus of thought on this topic. That we need a body of work on this topic.

Remembering Biafra got me considering what “things” I would put in my Atrocity museum as exhibits.

Here are a few things that came to mind. I have read all of these books and watched all of these films. There is no significance to the choices. This was just a random list of things that came to mind. I had over a hundred “artifacts” once I started thinking about it.

But, who wants to read all of that?

If you have additional ideas feel free to comment and add your testimony and thoughts. Somewhere on the internet there should be an Atrocity Museum.

Of things that shouldn’t be forgotten.

If you have never heard of the “Late Victorian Holocausts’” that’s because they don’t get a lot of mention in Western schoolbooks. The definitive book on this first “climate disaster” from early global warming, that I know of, is this one.

This book explores the impact of colonialism and the introduction of capitalism during the El Niño-Southern Oscillation related famines of 1876–1878, 1896–1897, and 1899–1902, in India, China, Brazil, Ethiopia, Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines and New Caledonia. It focuses on how colonialism and capitalism in British India and elsewhere increased rural poverty and hunger while economic policies exacerbated famine.

The book’s main conclusion is that the deaths of an estimated 60–100 million people (about 6–10% of the world’s population) killed in famines all over the world during the latter part of the 19th century were caused by the laissez-faire and Malthusian economic ideologies of colonial governments.

Davis examines in intimate detail the baleful relationship between imperial arrogance and a series of “climate disasters” that combined to produce some of the worst tragedies in human history.

Late Victorian Holocausts focuses on three zones of drought and subsequent famine: India, Northern China; and Northeastern Brazil.

All were affected by the same global climatic factors that caused massive crop failures, and all experienced brutal famines that decimated local populations. There were provinces in China where 90% of the population starved.

IN EACH CASE the effects of drought were magnified because of singularly destructive policies promulgated by different ruling elites.

Davis argues that the seeds of underdevelopment in what later became known as the Third World were sown in this era of High Imperialism, as the price for capitalist modernization was paid in the currency of millions of peasants' lives.

The film is concerned chiefly with four topics: the Chełmno extermination camp, where mobile gas vans were first used by Germans to exterminate Jews; the death camps of Treblinka and Auschwitz-Birkenau; and the Warsaw ghetto, with testimonies from survivors, witnesses and perpetrators. — Wikipedia

This documentary is 9 hours 26 minutes long. I have watched it three times over the years and I don’t need to watch it again. I think for me this artifact embodies the concept of the Atrocity Museum.

The documentary simply records the testimony of those who were there. Both the victims and the perpetrators. It speaks for the dead so that they aren’t forgotten.

Chronicling his experiences as a prisoner in Nazi concentration camps during World War II, and describing his psychotherapeutic method, which involved identifying a purpose in life to feel positive about, and then immersively imagining that outcome.

The book intends to answer the question “How was everyday life in a concentration camp reflected in the mind of the average prisoner?” Part One constitutes Frankl’s analysis of his experiences in the concentration camps, while Part Two introduces his ideas of meaning and his theory called logotherapy.

The book’s original title is Ein Psychologe erlebt das Konzentrationslager (“A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp”). Later German editions prefixed the title with Trotzdem Ja zum Leben Sagen (“Nevertheless Say Yes to Life”), taken from a line in Das Buchenwaldlied, a song written by Dr. Friedrich Löhner-Beda while an inmate at Buchenwald. The title of the first English-language translation was From Death-Camp to Existentialism.

— Wikipedia

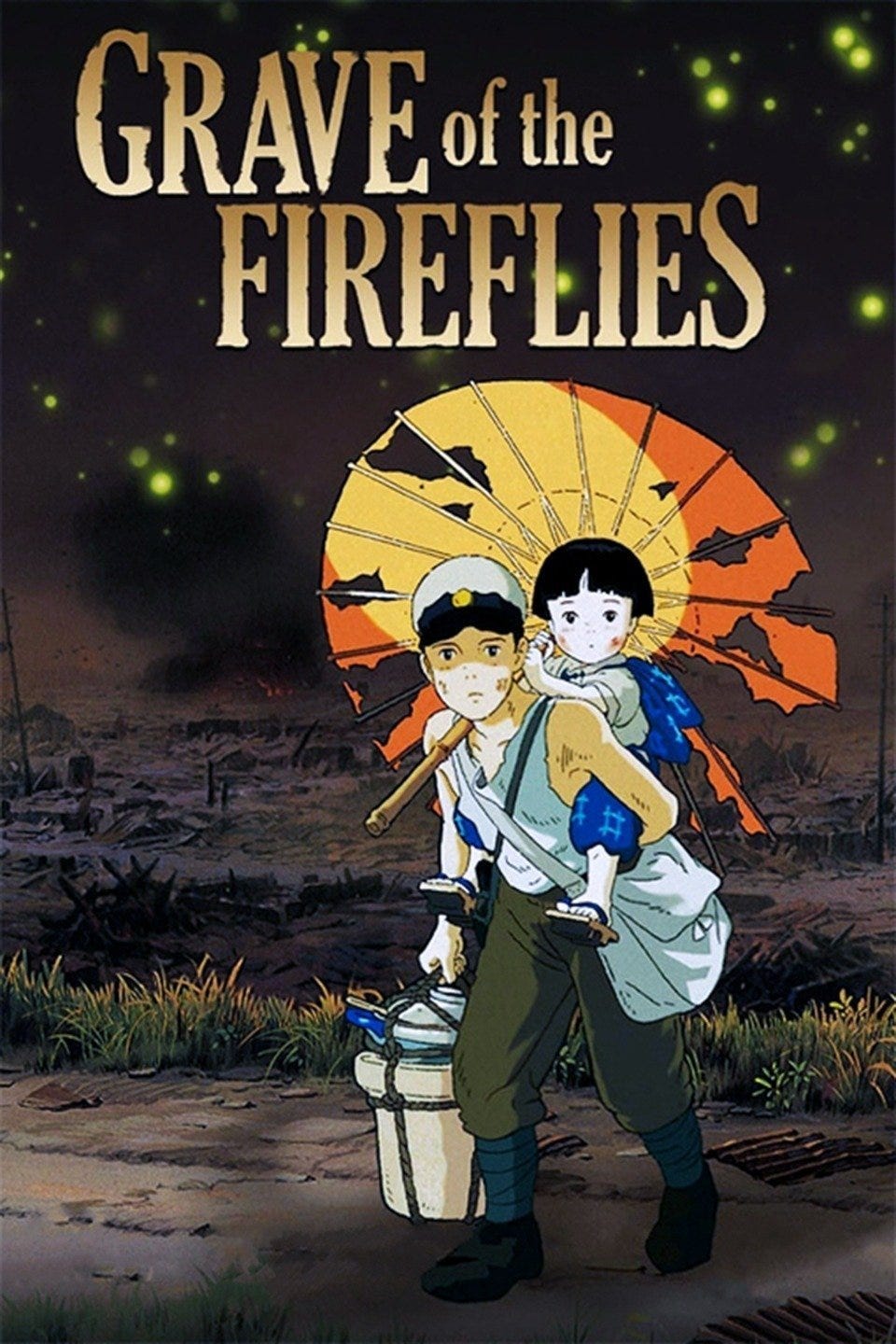

Akiyuki Nosaka relayed his personal experiences as a child during the war in the anime film Grave of the Fireflies, which tells the story of a young boy and his sister escaping from the air raids and the firebombings, scraping by on whatever rations they can find during last part of the war. — Wikipedia

If you can watch this without crying, you have no soul. Just the memory of watching this brings tears to my eyes. After all this time.

“Whatsoever you did for/to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for/to me” (Matthew 25:40, 45, NIV)

The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation (Russian: Архипелаг ГУЛАГ, Arkhipelag GULAG) is a three-volume non-fiction text written between 1958 and 1968 by Russian writer and Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

It was first published in 1973, and translated into English and French the following year. It covers life in what is often known as the Gulag, the Soviet forced labour camp system, through a narrative constructed from various sources including reports, interviews, statements, diaries, legal documents, and Solzhenitsyn’s own experience as a Gulag prisoner. -Wikipedia

These books changed my entire understanding of political science. What Solzhenitsyn is observing, is the nuts-and-bolts of how a “post revolution” population is broken onto obedience.

This is how you have to govern if you don’t have political legitimacy. You have to use fear and terror. This is what always happens after violent revolutions. Always.

One of the few movies about the Khmer Rouge’s “Year Zero” policy, a return to the agrarian ways of the past. The revolutionaries, under the direction of Pol Pot liquidated the entire existing “intellectual class” of Cambodian society.

Intellectuals were rounded up and sent to re-education camps. MILLIONS wound up in one of the Pol Pot regime’s Killing Fields.

Adapted from the book The Execution of Charles Horman: An American Sacrifice (1978) by Thomas Hauser (later republished under the title Missing in 1982), based on the disappearance of American journalist Charles Horman, in the aftermath of the United States-backed Chilean coup of 1973, that deposed the democratically elected socialist President Salvador Allende.

— Wikipedia

The atrocity I am referencing is the US involvement in this coup. The movie is a way to access that history.

A non-fiction book by American writer Dee Brown that covers the history of Native Americans in the American West in the late nineteenth century.

The book expresses details of the history of American expansionism from a point of view that is critical of its effects on the Native Americans. Brown describes Native Americans’ displacement through forced relocations and years of warfare waged by the United States federal government.

The government’s dealings are portrayed as a continuing effort to destroy the culture, religion, and way of life of Native American peoples.[1] Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1881 book A Century of Dishonor is often considered a nineteenth-century precursor to Dee Brown’s book.

— Wikipedia

My father had an intense interest in this topic. His grandmother (father’s side) was Comanche. He visited relatives on the Reservation when he was a small child.

I learned how to knap stone from him. How to track animals. How to hunt and how to kill. With both the gun and the bow.

Little Big Man is an early revisionist Western in its sympathetic depiction of Native Americans and its exposure of the villainous practices of the United States Cavalry. The revision uses elements of satire and tragedy to examine prejudice and injustice.

In 2014, Little Big Man was deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

— Wikipedia

While this movie may seem shallow at first glance, it is a searing depiction of the extermination of the Cheyenne Nation and the Plains Indians.

The Biafran War (6 July 1967 – 15 January 1970), was a civil war fought between Nigeria and the Republic of Biafra, a secessionist state which had declared its independence from Nigeria in 1967. Nigeria was led by General Yakubu Gowon, and Biafra by Lieutenant Colonel Chukwuemeka "Emeka" Odumegwu Ojukwu.

Biafra represented the nationalist aspirations of the Igbo ethnic group, whose leadership felt they could no longer coexist with the federal government dominated by the interests of the semi-feudal Muslim Hausa-Fulanis of Northern Nigeria. The conflict resulted from political, economic, ethnic, cultural and religious tensions which preceded the United Kingdom's formal decolonisation of Nigeria from 1960 to 1963.

Immediate causes of the war in 1966 included a military coup, a counter-coup, and anti-Igbo pogroms in Northern Nigeria.

Within a year, Nigerian government troops surrounded Biafra, and captured coastal oil facilities and the city of Port Harcourt. A blockade was imposed as a deliberate policy during the ensuing stalemate which led to the mass starvation of Biafran civilians.

They DELIBERATELY STARVED 2 MILLION PEOPLE TO DEATH AS A “MILITARY TACTIC”.

During the 2+1⁄2 years of the war, there were about 100,000 overall military casualties, while between 500,000 and 2 million Biafran civilians died of starvation.

The plight of the starving Biafrans became a cause célèbre in foreign countries, enabling a significant rise in the funding and prominence of international non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Biafra received international humanitarian aid from civilians during the Biafran airlift, an event which inspired the formation of Doctors Without Borders following the end of the war.

The United Kingdom and the Soviet Union were the main supporters of the Nigerian government, while France, Israel (after 1968) and some other countries supported Biafra. The United States' official position was one of neutrality, considering Nigeria as "a responsibility of Britain", but some interpret the refusal to recognise Biafra as favouring the Nigerian government.

Vonnegut's first hand account can be read here.

by Kurt Vonnegut

From Wampeters, Foma and Granfalloons, 1979

These are also Cultural Artifacts.

In my museum each of them would have a room and in that room the voices of the past would speak.

rc (first published on Medium 11/22) amended here 05/29/24

Addendum-

For the views of real professionals in this field, I recommend this book.

Exhibiting Atrocity: Memorial Museums and the Politics of Past Violence

AMY SODARO

Copyright Date: 2018

Published by: Rutgers University Press

I can only think about stuff like Gaza and all these others for a few minutes. Longer and I sink into a depression. I've learned to control the input into my mind to keep my mood stable. I imagine a huge vacuum cleaner with an On and Off switch attached to the far end if my mind. When I start to feel really bad, Bam! On goes the vacuum and I let ot suck all that out. I don't know how you can think about all of this stuff. I would go crazy.

Nice compendium, thanks.